The Fine Art of Letter Writing

Over this past weekend on our fun boondoggle of a vacation tour, The Good Man and I found ourselves up in Sonoma, California. Land of wines, a California Mission, and a fantastic historic plaza. Beautiful, wonderful Sonoma.

Another fabulous feature of Sonoma is that the writer Jack London lived there for many years. He and his second wife built an enormous home out in the tall redwoods, which sadly burned down, never to be rebuilt. They built a smaller cottage, and in fact, Jack London is buried there near the site of his home. This location, the ruins of the big house and London’s grave are all part of the Jack London State Historic Park due for closure in 2012 because of ongoing California budget woes.

Since both The Good Man and I are avid readers, we were thrilled to take a tour of the site.

One of my favorite parts of the museum was the many letters both to and from Jack that are on public display. He was quite the articulate one.

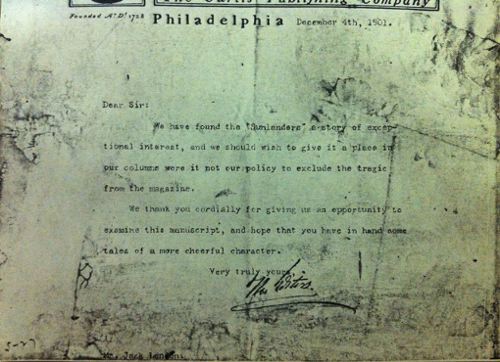

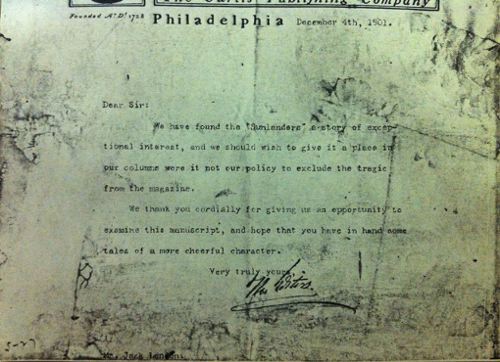

Here’s one that especially resonated with me. It’s a rejection letter from the editors at The Curtis Publishing Company in Philadelphia. I believe this was a query to the Saturday Evening Post.

Here’s what it says:

Dear Sir

We have found the “Sunlanders” a story of exceptional interest. We should wish to give it a place in our columns were it not our policy to exclude the tragic from the magazine.

We thank you cordially for giving us an opportunity to examine this manuscript, and hope that you have in hand some tales of a more cheerful manner.

Very truly yours,

The Editors

So, you know. Ouch. Your story? Rocked. But it’s sad. We don’t *do* sad. Write something happy, why don’t you?

Of course, this is also a very strong example, perhaps, of a writer not doing their homework before querying a magazine. I might be guilty of this.

This is but one of the many rejection letters that London received over the course of his notable writing career. He’d wallpapered his cabin in Oakland with them and there were many more to go. His first book was rejected 600 times.

Now that’s tenacity.

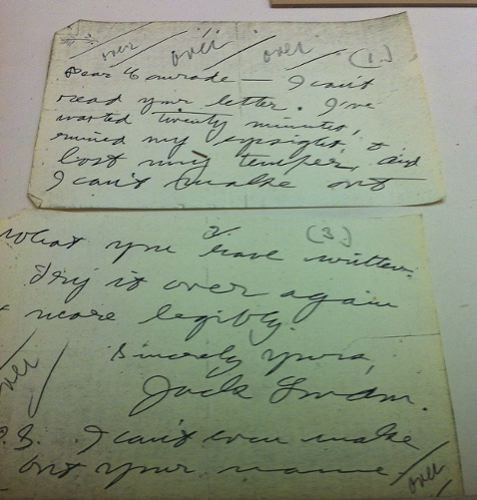

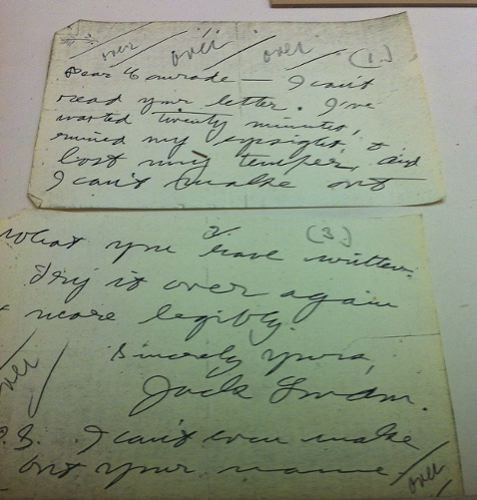

Then there’s this letter, a brief note included in the collection with no explanation:

It says:

Dear Comrade – I can’t read your letter. I’ve wasted twenty minutes, ruined my eyesight and lost my temper, and I can’t make out what you have written.

Try it over again and more legibly.

Sincerely yours,

Jack London

PS I can’t even make out your name

Oooh, rasty, rasty Jack. Love it.

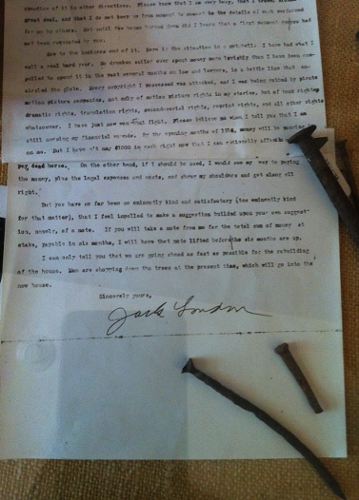

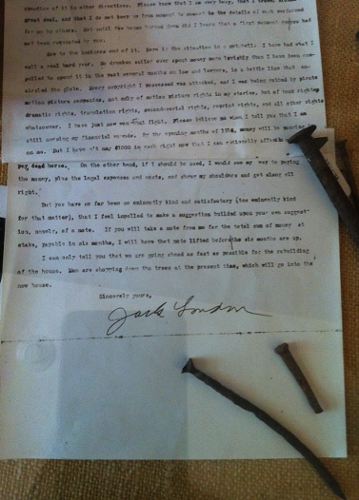

But my favorite, far and beyond the best of them all was a two pager regarding some delinquent payments.

It’s a doozy.

Here’s the text:

Messrs M. Clark and Sons,

Gentlemen:

In reply to yours of December 26, 1913, addressed to Mrs. Shepard, which Mrs. Shepard has kindly forwarded to me. I am glad she forwarded to you the letter I sent her the other day.

Before we get to the business end of it, let me tackle the mental end of it, namely, your inability to understand my remark that if you had collected the $1000 when it was due, I would not be pinched for it now. The funniest thing is, that it is just that $1000 I am pinched for now. Put yourself in my place: Mrs. Shepard had charge of the house building and the bill paying. I earned the money. Mrs. Shepard always let me know roughly what bills and expenses were paid each month. Anything that was left over I spent. Naturally, since the $1000 was not collected at the time it was due, it was left over, and I spent it. You know what a dead horse is—–this $1000 is now a dead horse to me. I cannot unspend the spending of it in other directions. Please know that I am very busy, that I travel around a great deal, and that I do not keep up from moment to moment in the details of work performed for me by others. Not until the house burned down did I learn that a first payment due you had not been requested by you.

Now to the business end of it. Here is the situation in a nutshell: I have had what I call a real hard year. No drunken sailor ever spent money more lavishly than I have been compelled to spend it in the past several months on law and lawyers, in a battle line that encircled the globe. Every copyright I possessed was attacked, and I was being robbed by pirate motion picture companies, not only of motion picture rights in my stories, but of book rights, dramatic rights, translation rights, second-serial rights, reprint rights and all other rights whatsoever. I have just now won that fight. Please believe me when I tell you that I am still nursing my financial wounds. By the opening months of 1914, money will be pouring in on me. But I haven’t any $1000 cash right now that I can rationally afford using to pay a dead horse. On the other hand, if I should be sued, I would see my way to paying the money, plus the legal expenses and costs, and shrug my shoulders and get along all right.

But you have so far been so eminently kind and satisfactory (too eminently kind for that matter), that I feel impelled to make a suggestion builded upon your own suggestion, namely, of a note. If you will take a note from me for the total sum of money at stake, payable in six months, I will have that note lifted before the six months are up.

I can only tell you that we are going ahead as fast as possible for the rebuilding of the house. Men are chopping down trees at the present time, which will go into the new house.

Sincerely yours,

Jack London

This letter made me laugh out loud. Makes me want to take a few lines from his work the next time I have to write a gripe to someone who has ticked me off.

Here’s a good example: Dear Sirius Radio, it’s a dead horse, I’m not going to sign up with your service again. I’ve been spending money as lavishly as any sailor ever did (*cough*iPad*cough*) and I’m tapped out. Now go away.

Good ol’ Jack. One hell of a writer.